Automatic conspiracy

There's something incredibly compelling about big conspiracy theories. Secret groups of well-connected people running the world like a shadow government, tentacles reaching into every boardroom, every cabinet meeting... that sort of thing. Of course, there's no evidence for any grand-scale conspiracy and, although there are examples of small scale conspiracies here and there, even those are pretty rare. But maybe the issue is that conspiracy-hunters are looking for the wrong thing.

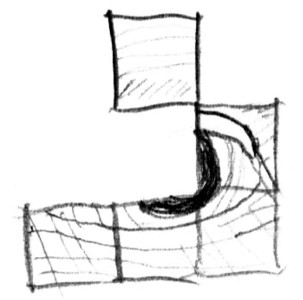

Inherent in the idea of a conspiracy is an agreement between people, something explicit and human-powered. But if the past century has taught us anything, it's the incredible power of systemised and automated processes, with as few people involved as possible. Surely a conspiracy that could be effective on a global scale would have to be very different from what we'd imagine. It wouldn't be run by people, but by processes. A kind of automatic conspiracy.

Let's imagine some nefarious secret organisation wants to keep people stuck docilely wasting time on their computers all day for some Evil Purpose. The conspiracy would set about researching ways to make computers addictive, give them features reminiscent of slot machines, and carefully optimise every facet of their operation to maximise those compulsive qualities. A spooky theory to share with your fellow conspiracy buffs! But of course it is actually happening, and the only part that isn't true is that there is some secret cabal driving the process.

Instead, it's just a series of fairly straightforward incentives. People value free things irrationally highly, so it's a good idea to make your money from advertising or microtransactions instead. Both of those work better the more you get your users to engage with your product. And, of course, you're competing with all the other products to do this most effectively. The modern analytics-driven software world lets you experiment on your users and optimise every decision to maximise engagement. If that engagement happens to look a lot like addiction, well, I guess our users just really like us.

If a group of people were driving this process, we would of course ask them to justify its ethics. But there is no group. If there's a puppetmaster pulling the strings it's none other than our old friend the invisible hand: each person acting individually is acting collectively, as long as the incentives are aligned. And because what we see doesn't look purposeful, we don't question its purpose.

But the systems that we have built give rise to far greater conspiracies than we could dream of hatching with mere humans in a darkened room.